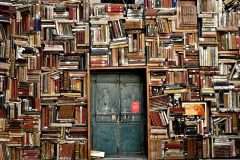

For all lovers and connoisseurs of English classical literature, but directly for admirers of the writer’s talent, we reveal to you the secrets of the Dickens family.

Charles’s father, John Dickens, served as an officer in the financial department of the maritime department. When he had a son, he was twenty-six years old. He married in 1809 to the eighteen-year-old Elizabeth Barrow, daughter of Charles Barrow, who held the position of chief cashier in the same department, associated with great financial responsibility.

There is a detailed pedigree of the Dickens family and the Barrow family, but these are only one names, and we can not get from them any idea of the writer’s ancestors. Charles Dickens would probably be just glad about it. For Dickens, man exists only on his own.

However, no matter how he despised hereditary privileges, he could not, being a representative of the middle class of Victorian England, not care at all about his origin and position in society.

Dickens liked to talk about his father’s Staffordshire ancestors and, regrettably, until the end of his days used the fake noble coat of arms as an ex libris. However, having become a world-renowned writer and having truly established himself in society, he could already be himself and now directly declared that he had achieved his place in life without any help, stubbornly following his own path.

From a social point of view, Dickens began his life outside the circle to which he dreamed of belonging. According to people who have long known the Dickens, “this family was not without ambition”.

Before his inevitable catastrophe, his father, who had no money, was constantly experiencing periods of relative prosperity and times of complete lack of money, and this made Dickens even more stress that they were not simple. However, in addition to monetary difficulties, there was also another reason for the precarious position of the Dickens in society. Both parents had their own family secrets, although of a completely different nature.

First of all, Oxford Street in London lived alone Dickens’s grandmother, a respectable lady who had accumulated a decent fortune about a rainy day. But although she was really a very respectable person, in the past she was a servant. True, she served in the homes of the highest aristocracy – first a maid in the London house of the Marquis of Blandford, and then, before she finally retired, the housekeeper at the glorious Marquis of Crewe. And Dickens’s grandfather, who died long before his birth, also served in Crewe’s house as a butler. Of course, if someone asked Dickens about the members of the famous name Crewe, they would have respected the old woman who served them with great respect, but all the more would have laughed at the noble claims of the footman’s son, and besides John Dickens, about whom they had time to find out that he’s a worthless fellow and always begs money from his mother. But all this seemed to John Dickens in a completely different light, although it was Crewe who got him a place in the financial department of the maritime department. It is not easy for an official to admit that his parents are servants, even if he owes his position to the patronage of their owners. In addition, he married the daughter of the chief cashier of his administration. In the family of his wife, many were noble, and her brothers were educated and showed great hope. It was better to push the ancestors from the people somewhere, and this important circumstance should always be remembered when evaluating the situation in which the writer grew up, for, in any case, his father deliberately suppressed the memory of his childhood spent among the servants.

Without a doubt, all this was done more with an eye on Mrs. Dickens’ noble relatives, and yet she too had something to hide. Her father, Charles Barrow, a respectable and majestic cashier who quickly made a career (rumor claimed that he was an illegal offspring of some aristocrat), for nine years, as it turned out, systematically faked his reports. During this period, he has arrogated to himself something about six thousand pounds. This scandalous discovery occurred two years before the birth of his grandson. Fearing prosecution, Charles Barrow fled abroad and sixteen years later (Dickens was already fourteen years old) then died on the Isle of Man, which was not subject to English jurisdiction. It is difficult to admit that the runaway relative did not complicate the Dickens’ social situation, however, to the credit of our institutions, this did not have a significant effect on the career of John Dickens, nor on the fate of his brother-in-law Thomas, the son of the escaped; and although Dickens’ parents understood that Charles Barrow dishonored them, this did not stop them from giving their son the name of the lost grandfather.

Nevertheless, if social conditions forced to keep silent about the grandmother on the part of the father, then the grandfather’s illegal position gave rise, of course, to some vague, mysterious mention of this missing relative from the mother. In any case, such sociable people, like the young parents of Dickens, had to hide behind false phrases like: “my childhood spent at Crewe’s estate” or “my father, living abroad”. Deception and mystery are usually perceived by us in Dickens’ novels as a melodramatic device, but in reality these were facts of life, perceived from childhood.

The main feature of Dickens’s parents, captured in his novels, was their need to present themselves as if from a stage. The little we know about their lives reinforces this impression.

John Dickens was remembered by people for his actingly acclaimed speeches. About her mother, Elizabeth Dickens, the writer recalls that when she was already an old woman she wanted to appear in her mourning something like “Hamlet in a Skirt”. It was an expansive couple, and so were their children. Dickens was a temperamental person, prone, as we shall see, under other circumstances to fall into hysteria. His beloved brother Fred was famous for the art of imitation. There is a story about how in 1842, when Charles and Fred rested together in Broadstairs and sailed on a ship, they were tirelessly entertained, shouting out joking commands to each other, made up of almost real marine terms: “Pull up your capstan!”, “Strengthen a peg on his mizzen!” etc. Fred and younger brother Augustus took an active part in amateur performances, which Dickens was fond of. The elder sister of the writer, Fanny, was his constant partner when they entertained children with poems and singing duets. As for melodrama, the subsequent life of the Dickens, Fred and Augustus brothers – this change of financial setbacks and family storms – fully confirms the existence of a certain Mikoberian tradition inherited from parents.

Dickens was only seven months old when material difficulties forced his parents to move from the house where he was born, to another, worse and cheaper; so then they moved all the time while he lived under the parental shelter, or, more precisely, the shelter. But in 1814, a few months after his second birthday, his father received a post in London. It’s funny that Dickens, who glorified London with his descriptions, like Balzac – Paris, and Dostoevsky – St. Petersburg, subsequently could not remember anything special about his then life in London, from where he left a four-year-old child. Then, in 1816, John Dickens was assigned to Chatham, one of the main shipyards at the mouth of the Medway in Kent, thirty miles southeast of London. Here Dickens first lived in house number two on the Ordnance Terrace – a nice and cozy little house of this quarter, where middle-class people lived, and then, since 1821, probably due to the extravagance of his father, in a less respectable area, at St. Mary’s Place, not far from the shipyards. Obviously, life here proceeded just as in Portsmouth. However, at Chatham, Dickens felt happy and always recalled this time as the best period of his life.

Source: e-reading.club

Good luck in finding.